We held an event “not Divide but Share” – Education in Sweden Vol.3: Everyone joins in making rules” on September 24th, 2018 at KOKUYO Studio in Shinagawa, Tokyo.

There were about 60 people at this event, some of who worked at council or education-related job, and others were parenting, and so on.

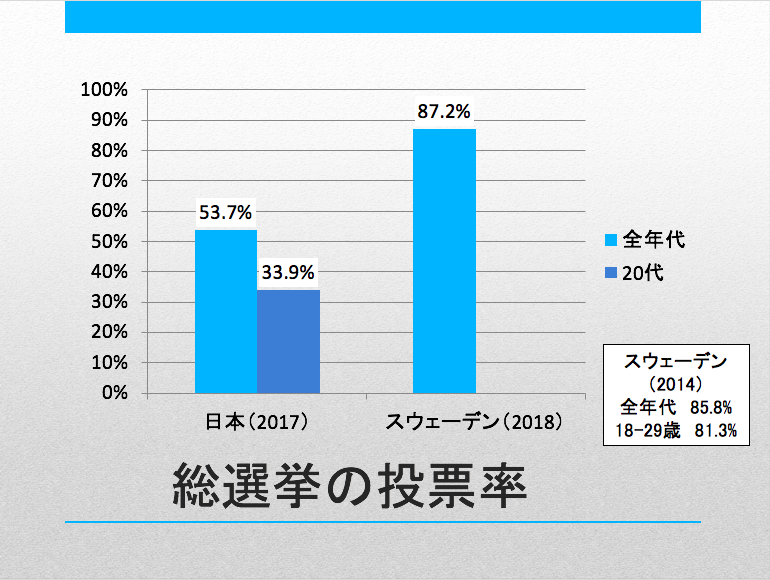

81/33 … The difference of youth voter turnout between Sweden and Japan

We started the workshop by asking questions about the number “81% vs. 33%”, which is youth voter turnout of Sweden and Japan, why there was so much difference between them.

Opinions from the participants were as follows:

・In Sweden, it is not a taboo to join in politics even from elementary school. I suppose that’s the reason why the youth voter turnout is high.

・In Japan, people feel like that it does not make a difference to vote any candidate or political party. In Sweden, on the other hand, people know the difference of each party and the impact of political decisions affecting their daily lives; I think that’s why they vote.

Mr. Kenji Suzuki, the guest speaker of the event, added the comment: “In Sweden, each party has to distinguish themselves by showing the uniqueness in their argument because the voters are so interested in politics. It’s like two sides of the same coin, while many Japanese people think that it does not make any difference by voting any political party.”

“Swedish pupils should decide what they learn on their own”

Swedish general election took place just two weeks before the event and its voter turnout reached 87.2%, higher than the previous election. Why do Swedish people take social issues as if it’s his/her own? How do they nurture the attitudes to try to influence politics through voting?

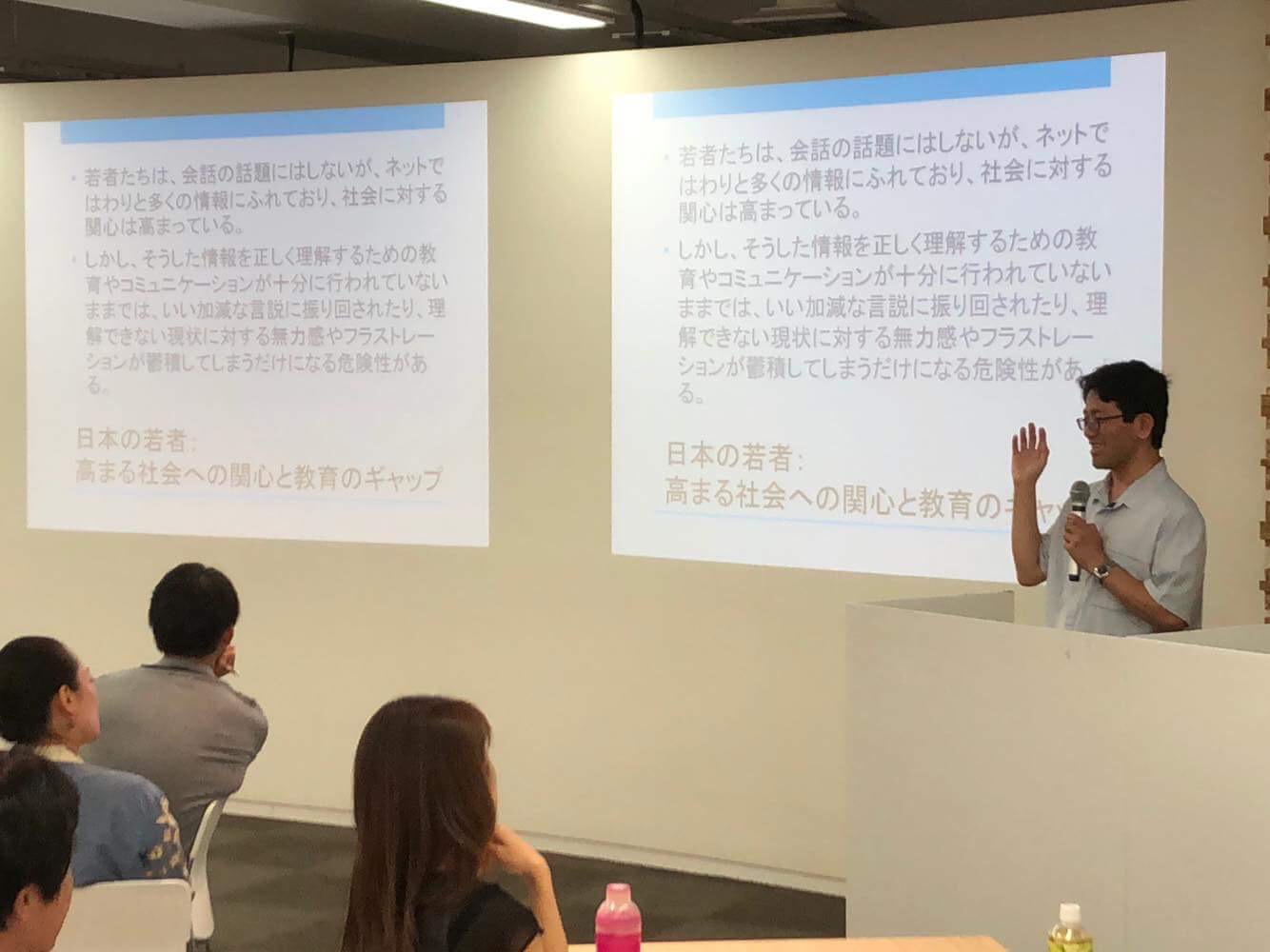

<source: from Mr. Suzuki’s presentation>

As a hint for this status, Mr. Suzuki firstly explained about the Swedish national curriculum, the Swedish Education Act.

“The school should be open to different ideas and encourage their expression. It should emphasize the importance of forming personal standpoints and provide opportunities for doing this.”

“It is not in itself sufficient that teaching only imparts knowledge about fundamental democratic values. Democratic working forms should also be applied in practice and prepare pupils for active participation in the life of society. This should develop their ability to take personal responsibility. By taking part in the planning and evaluation of their daily teaching, and being able to choose courses, subjects, themes and activities, pupils will develop their ability to exercise.”

* source: Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare 2011 ( https://www.skolverket.se/sitevision/proxy/publikationer/svid12_5dfee44715d35a5cdfa2899/55935574/wtpub/ws/skolbok/wpubext/trycksak/Blob/pdf3984.pdf?k=3984 ), citation from P6: Objectivity and open approaches and P7: Rights and obligations.

The curriculum mentions even that Swedish pupils should decide what they learn on their own. However, would the class go well in this way?

Mr. Suzuki explained that one of his friends, a Swedish teacher, told him that Swedish teachers think out how they motivate their pupils: the teachers do not tell pupils directly what they should do, but try to “induce” to do what teacher’s want them to do.

As a result, pupils feel that “they learn what they choose” and have a higher motivation.

Social Studies in Swedish primary school: Teaching detailed process of how to affect society

The social studies textbook 4th -6th grade in Swedish primary school is very different from Japanese one. The opening sentence of the textbook is as follows:

“Have you ever thought deeply what society is? Let’s think about how to answer this question.”

“All societies change… Norms also could change. For example, if you want to change your hair style or fashion which is thought to be different by many people, just continue doing it. The others and the norm might change their mind that your style is cool.”

Mr. Suzuki points out that many Japanese people would say “you should follow the rules” but never “try to change the rules, it might change”. “For example, when you do a play on stage in Japanese school, the pupils could decide what roles each one plays in a democratic way. In Swedish school, the pupils could even throw a question if they should do a play on stage in the first place.

In addition to that, the Swedish textbook says that you should be an opinion leader to influence a decision by others’ support. It also shows the detailed process to achieve it such as collecting signatures from friends or family, contributing to the local paper, leading a demonstration march, contacting directly a politician and so on. Furthermore, everything connects “to be listened”, even spelling correctly and using SNS properly: this is how they motivate pupils to learn.

Mock election in school: voting for real parties

In Sweden, pupils in lower secondary school take part in the “mock voting in school”; it is carried about a month before the real election by each school and they votes for real parties. The result is disclosed after the real election to prevent influencing the real result. Pupils talks about politics even after election.

As mentioned above, Swedish people are proactive to participate in election activities. Meanwhile, they are cautious to keep political neutrality in school just as in Japan. What is different is how they deal “neutrality”. They invite politicians from all the parties to the school with certain criteria such as “having a seat in a Diet”, whereas in Japan, they try not to talk too much about politics in schools to avoid troubles.

“Nowadays Japanese youth also growing their interest to the society and they can get information from the internet. Meanwhile, they are not much trained to read critical: it might lead the youth feel helpless among the biased information and groundless rumors. I think the first step for nurturing democratic attitudes is to question the existing rules.”, Mr. Suzuki concludes.

Group discussion

After presentation by Mr. Suzuki, it moved on to Q&A session and Mr. Suzuki and Swedish international student from his research group answered the questions and exchanged opinions with participants.

・What do you think is superior in Japanese education? (raised by a high school student)

> <from Mr. Suzuki> If you see the result of PISA, Japan is ranked higher. I think it’s due to the learning method, that Japan directly teaches the knowledge, and it’s a strength of Japanese education. (In Sweden, on the other hand, they teach indirectly to let pupils have their own motivation.)

Meanwhile, I sometimes wonder if it’s really a good point. It might be that we are learning what AI could also do. What is needed in the future might come out from a Swedish way.

・If you do not have an opportunity to nurture the awareness of social issues, you cannot decide which party to vote. Is there any opportunity in Sweden that you meet the social issues or reflect your own thoughts towards it at school?

> <from Mr. Suzuki> Almost all the textbook I introduced today deals about such staff. Find a problem / issue by yourself, summarize your thoughts on it, and discuss. We might do the similar things in Japan as well, but not much on the real politics.

> <from Fredrik> We discussed a lot at elementary school. For example, “How to solve environmental problem”. Someone says “Let’s not use car, to protect environment.” and then other says, “It’s not a good solution, because you cannot go to work without a car” etc. I remember that we discussed a lot like that.

Then we had a Fika, the Swedish version of coffee break, and went to group work how to change rules in democratic way. Participants discussed about existing rules in school or company, the background of rules and what we should do to change them.

Feedback from participants (abstract)

・I came here to get some clues for what we could do in Japan regarding democratic education. I felt that I should learn more about it myself, as well share what I learned today with my family.

・I think I could get an answer through the event to why we learn. I also understood how to encourage people to have their opinions by asking questions and letting them think what they need. Furthermore, I’d like to tell the importance of respecting others’ opinion if you want to have your opinion heard.

・I felt it is important to tell children that norms / rules are controllable, they can change.

・I am a teacher and I joined this event being invited by my friend. I listened to the presentation imagining my workplace. In my experience, it seems that smart pupils are more to follow rules and they do not want to change them: I thought this attitude is reflected in the current politics in Japan.

・The presentation was quite interesting as I majored in party politics at graduate school. I am sure that Japanese children should learn and practice more about how to express their opinion and discuss something as in Sweden. In addition to that, I wish there were some learning tools for Japanese adult who haven’t taken such education because it is very important for us, too.

・Though it is hard to change the social system as a whole, there must be something the individual could do for social change. I was inspired by Mr. Suzuki that he discuss actively with his son: I want to do it with my children.

・It caught my attention that there is a big difference in how to educate democracy between Japan and Sweden, despite the similarity between them. I suppose the key point is not just being independent but how to take responsibility for one’s action.

・I am a high school student and it was a precious time to talk with people with various experiences. I got to know how Japanese education could improve more by comparing Japan and Sweden.

Report by: Rie T.